Awesome Building of the Month:

May 2024

The Charlie Santa Monica at Yale

Smooth Mix!

By Frances Anderton and David Kersh for FORT:LA

Address: 2822 Santa Monica Blvd., Santa Monica, CA 90404

Developer: LaTerra Development

Architect: Tighe Architects

Contractor: LT Building/Zwig Construction

Completed: 2022

Type of housing: Inclusionary/Mixed Income

Project mix: Total 50 apartment units (studios, 1, 2 and 3 bedrooms) with 4 low-income affordable units, 10,000 sq. feet of retail, fitness, coworking areas

Rent: Market Rate: Range from $2,924 to $5,525; Affordable: from $591 to $665

Affordable Housing Application: Santa Monica Housing Office

What is The Charlie Santa Monica at Yale?

The Charlie Santa Monica at Yale is part of “The Charlie Collection,” a brand of mixed-use, boutique complexes built by the private developer LaTerra. This one is in the City of Santa Monica, at the corner of Yale St. and Santa Monica Boulevard. It was designed by the noted architect Patrick Tighe and consists of 50 apartments atop retail and office spaces at grade level. It is close to bus lines, a few blocks from the Expo Line, and the Media District (Lionsgate, Universal, Hulu, and more).

The building is a gentle three stories high, with a facade whose mass is broken down by a pleasing grid of horizontal and vertical windows, recessed balconies and white metal corrugated cladding and balcony rails. The design’s simplicity and balance is slightly set off-kilter by tilting columns that hold up the two stories of apartments. Residents share a courtyard, landscaped terraces and a rooftop with a spa, all of which provides respite from the four-lane thoroughfare. There are two levels of subterranean parking as well as lounges, a game room, a gym, and shared office spaces. “You know, it’s sort of a boutique hotel vibe,” says LaTerra director Chris Tourtellotte, adding, “There’s a community aspect to it, where we do events, and there’s opportunities for tenants and residents to meet each other and become friends.”

The rents are boutique, at prices ranging from almost $3000 to around $5500, for studios, and 1, 2, 3 bedroom apartments. For four households, however, living here is extremely affordable, at under $700 per month. This is an example of “inclusionary zoning,” where a market-rate building includes a certain percentage of “affordable” units. That cut is typically between 5 and 20%. Here it is 8%, and the dwellings are for households in the extremely low income level of 30% area median income (AMI).

What Makes it Awesome?

Tighe’s design is gracious in form and scale, and artful in composition, while the sloping columns give it verve. The two stories over retail make for an unobtrusive height though with the width of the boulevard it could arguably have gone a story higher and not overwhelmed. Patrick Tighe, a prolific architect of both market-rate and affordable housing that are adventurous in material and form, explains his visual strategy as “a composition of white.” Metal panels are used in various settings, “all rendered in shades of white that vary in texture and transparency…Accent colors of blue and green provide a subtle (coastal) contrast at the recessed balconies.”

Explain Inclusionary Zoning

The monthly “awesome” projects shown to date have been 100% Affordable Housing (AH), meaning all rents are subsidized, per a covenant lasting typically a 55-year period. They were developed by non-profit developers using tax credits and multiple public funding sources. The developers earn a one-time developer fee, rather than an ongoing return on its investment through the monthly rental income on all the units.

The plus side is that rents are kept affordable, as long as the resident’s income meets the qualifying AMI; a challenge is that development costs can be higher than in market-rate buildings. That is due to factors including the complexity and length of the financing and planning process, prevailing wage requirements for labor, and many bureaucratic hurdles. Moreover, many 100% Affordable projects are built in lower-income areas where land is cheaper and residents lack access to high-opportunity jobs, better schools, parks and recreation facilities.

So municipalities have turned to another strategy to build affordable housing in high-opportunity zones: Inclusionary Zoning (IZ), also known as Mixed-Income Housing. That’s when the developer of a market-rate building has to include a percentage of units at an affordable rent. In these mandatory IZ programs, cities establish the percentage of affordable units the developer must provide, and then give them the option to build the affordable and market units in the same structure, or on separate sites. Or developers pay into a housing trust through what is called an “in-lieu fee.” There are also voluntary programs to promote mixed-income housing, described below.

There are Four Affordable Units at The Charlie. How does that Help with Housing?

It’s true, four low-income units out of fifty sounds like small potatoes. Inclusionary programs do not achieve AH at scale within one building. However, if you aggregate all the inclusionary units in mixed income housing, you have spread a large number of affordable units across LA County,

Although the majority of affordable housing units are produced with public subsidies, this past decade has seen a dramatic increase in the number of mixed-income housing projects. Since there are no public subsidies involved, taxpayers are not paying for them, and they are cheaper to build. A typical market-rate unit in a West Hollywood or Santa Monica building might cost around $600,000 for a private developer to build. If the percentage of AH required is too high then the math won’t work. So yes, it seems like dribbles, five units here, 10 units there, but they add up.

LaTerra, the developer of The Charlie Collection, is one of the most active multi-family residential developers in Los Angeles County. It has between 2,000 and 3,000 housing units in various stages, from entitlement to completion and renting, with approximately 10% of them as affordable. That’s around 270 new homes for low-income households. Cities they have worked in include Burbank, West Hollywood, Santa Monica, and in the City of Los Angeles, the neighborhoods of Venice, Echo Park, and Downtown LA. The company works with several designers, including Tighe Architects, Office Unlimited, and Urban Architecture Lab/TCA.

Are the “Affordable” and Market-Rate Units Different?

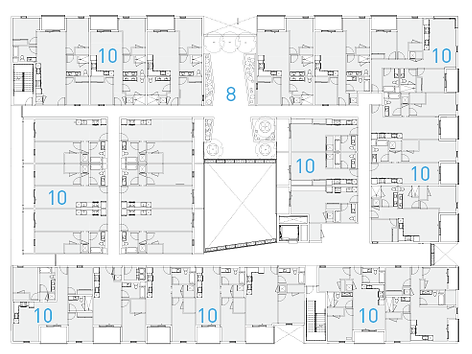

No, says LaTerra Managing Director Chris Tourtellotte. He explains the city’s rules as follows: “Units have to be dispersed throughout the building pretty evenly and randomly. You can’t cluster them together, and the unit mix of the affordable has to be representative of the overall unit mix.” He says you also can’t change the specifications and the finish level of the affordable units. “So they look identical to the market-rate units, they have the same amenities, the same services the same, all the same finishes, countertops, cabinets, appliances, so they look identical, you would not know the difference.” In this Charlie there are 6 studios, 24 one bedrooms (2 AH), 12 two bedrooms (2 AH) and 8 three bedrooms.

However, you may have heard of the “poor door,” the infamous separate entrance for the low-income tenants in luxury New York buildings with mandatory affordable units. Even in Santa Monica there is some wiggle room. The city prescribes that the “design of the affordable housing units shall be reasonably consistent with the market-rate units in the project.” Some developers do make distinctions, through subtleties like different countertop treatments or through putting the affordable units in an entirely separate building (see, Alternative Means of Compliance, below).

Isn’t This Social Engineering?

Yes, if you believe that people of different incomes should not live alongside each other as is the norm in many old cities. It is fairly radical in LA where housing is stratified and denotes wealth. In inclusionary projects like The Charlie Collection, the market-rate units essentially subsidize the affordable ones. Proponents argue this is a way to expand economic opportunity, and create a more diverse mix of tenants. Opponents, and that includes some developers who do not like being pressured into including affordable units, believe that when the difference between incomes is too extreme, it can create tensions.

Challenges in Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning

Housing experts in favor of untrammeled construction of new housing question Inclusionary Zoning on the grounds that it produces a limited supply and may even increase housing costs in general, and reduce overall future housing production. Shane Phillips, author of The Affordable City, cautions that, “one of IZ’s fundamental shortcomings is that it does not address—and likely exacerbates—the housing scarcity that drives higher rents and home prices. It improves housing affordability for a few at the risk of worsening affordability for many, and it taxes precisely the activity needed to ameliorate the housing shortage and bring down rents: development.”

Tourtellotte is supportive of the strategy, if the inclusionary requirements are reasonable and sensitive to the specific location and the area’s jobs/housing balance so they can make it work financially. Plus, he says, the rules of the road have to be clear from the start. “Where it becomes challenging,” notes Tourtellotte, is if laws are passed or changed sort of midstream, because you’ve got to bake [the costs of the affordable units] into your projections and your pro forma. As long as that’s known, it becomes easier to wrap your arms around the other question, which is does it pencil? The project still needs to pencil.”

Tell us More about the Other Mixed-income Housing Programs?

Many Southern California cities have mandatory inclusionary requirements; these include West Hollywood, Santa Monica, Long Beach, Burbank, Pasadena, Culver City, Beverly Hills, and Pasadena. Other options are:

- Alternative Means of Compliance

These policies are legally required to provide alternative means of compliance that include: paying in-lieu fees to a city’s housing trust fund, off-site construction, or acquisition and rehabilitation of existing units.

- City of Los Angeles Transit Oriented Communities (TOC)

The City of Los Angeles has a voluntary Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) program which loosens up red tape and gives developers incentives and waivers (from code requirements limiting height and size, and from set-back and open space requirements) in exchange for providing a percentage of on-site AH units. It applies to locations close to transit stops. This program is also used by 100% AH developers to build larger buildings.

- State Density Bonus

The State Density Bonus provides developers with a menu of incentives, waivers and concessions that allows them to build more units, add more height, or receive waivers from code requirements as with TOC, enabling market-rate developers to maximize the development potential of a piece of land and cross-subsidize the affordable units. This has become one of the main games in town to increase the number of affordable units across the board.

Do These Programs Solve the Affordable Housing Crisis?

No, but in a very complicated housing ecosystem, every little helps. In LA right now it is impossible to build at the scale of the problem. Some other cities and countries try and accommodate people who cannot afford market rents by owning, building and managing public, or “social,” housing. The US Federal Government used to do so too. But government investment dropped to a trickle in the last half-century, and today there are scarce public subsidies for the low-income affordable projects of the type we’ve focused on in Awesome and Affordable.

Other cities and countries allow untrammeled construction to maintain a supply of affordable housing. Take Tokyo, Japan or, says Tourtellotte, a high supply market like Austin, Texas. There, “rents are down 14%, more than any other city in the country. So it is a true statement, that the more supply you produce, the lower rents will go. And in doing so, you create rental rate levels that will work for the majority of renters.” In California, he notes, “rents are too high, and we need more supply. And I think that including an inclusionary piece in the project is a good idea.”

Call To Action

If you like the concept of inclusionary projects, express your support for the City of LA’s Mixed Income Incentive Program, which is part of its Citywide Housing Incentive Program (CHIP) Ordinance, currently being drafted. The Mixed Income Incentive Program will provide developer incentives for building more affordable housing as part of low scale/low rise housing projects in City’s high and highest resource areas. It will also codify and expand the Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) affordable housing guidelines.

Image Credits: From top of page, 1-7: The Charlie in Santa Monica at Yale. Image 8: The Charlie at Broadway and Cloverfield; Image 9: The Charlie Echo Park. All images courtesy of LaTerra Development and Tighe Architects, except 2 and 7, by Frances Anderton.