Awesome Building of the Month:

February 2024

A Vintage Trio

Revived with Brio!

By Frances Anderton and David Kersh for FORT: LA

28th Street YMCA, Paul R. Williams Apartments, Dunbar Village

Three historic buildings in South Los Angeles that had gone into decline were given a new life in the 20-teens, as low-income homes! Two were originally designed by Paul R. Williams: the 28th Street YMCA, and the Angelus Funeral Home, now the Paul R. Williams Apartments. The other is the former, legendary Dunbar Hotel on Central Avenue, now Dunbar Village. The three complexes, which are very close to each other, brought together housing builders, community activists and preservationists in complex funding and development processes. They show how existing buildings can be upcycled into livable places that also sustain the community’s connection to its past. The City of Los Angeles is currently expanding its Adaptive Reuse Ordinance, and projects like this paved the way.

28th Street YMCA

Address: 1006 E. 28th St. Los Angeles, CA 90011

Developer: Holos Communities (formerly Clifford Beers Housing) and Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD)

Architect: YMCA, Paul R. Williams; 28th Street YMCA and apartments, Koning Eizenberg Architecture

Contractor: Alpha Construction

Date: YMCA, 1926; 28th Street Apartments, 2012

Type of housing: 100% Affordable

Dwelling mix: Studios

Listing: LA Housing Department, Affordable and Accessible Housing Registry

A Community Hub Reborn

28th Street in South Los Angeles a mostly residential street, with soft-colored clapboard houses, chickens pottering along the street (the day we visited) and then, looming over them all, a 4-story, stately Spanish colonial revival building with ornate door and window frames. This was a YMCA, complete with community rooms, brick-walled gym, and a pool. It was designed by Paul R. Williams in the 1920s to serve the Black community in South LA at a time when pools were racially segregated and few were available to African Americans. It was a hub for politicians and society figures.

New life for a landmark

Times changed, the building fell into decline and in the 20-teens the nonprofit developer Clifford Beers Housing (now Holos Communities) and the South-LA based nonprofit Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD) worked with Koning Eizenberg Architecture to create housing in a striking convergence of old and new. The ground floor became a youth education and workforce development center with a computer lab open to the community, run by CRCD staffers decked out in green company T-shirts. They turned the upper floors of the YMCA building into permanent supportive housing dwellings.

Then they added a new 4-story building at the back of the site, with studio apartments with windows on both sides for cross-ventilation. There are a total of 49 dwellings, with 30 of them permanent supportive housing. Young people from CRCD’s South LA Youth Build program assisted with the construction. “Paul Revere Williams served as a champion and example for minorities during a time when racial discrimination and segregation was pervasive in Los Angeles,” said Cristian Ahumada, Executive Director and CEO of Holos Communities. “The 28th Street Apartments honors his legacy, by creating a space that fosters community and provides economic mobility for those most vulnerable.”

What Makes it Awesome?

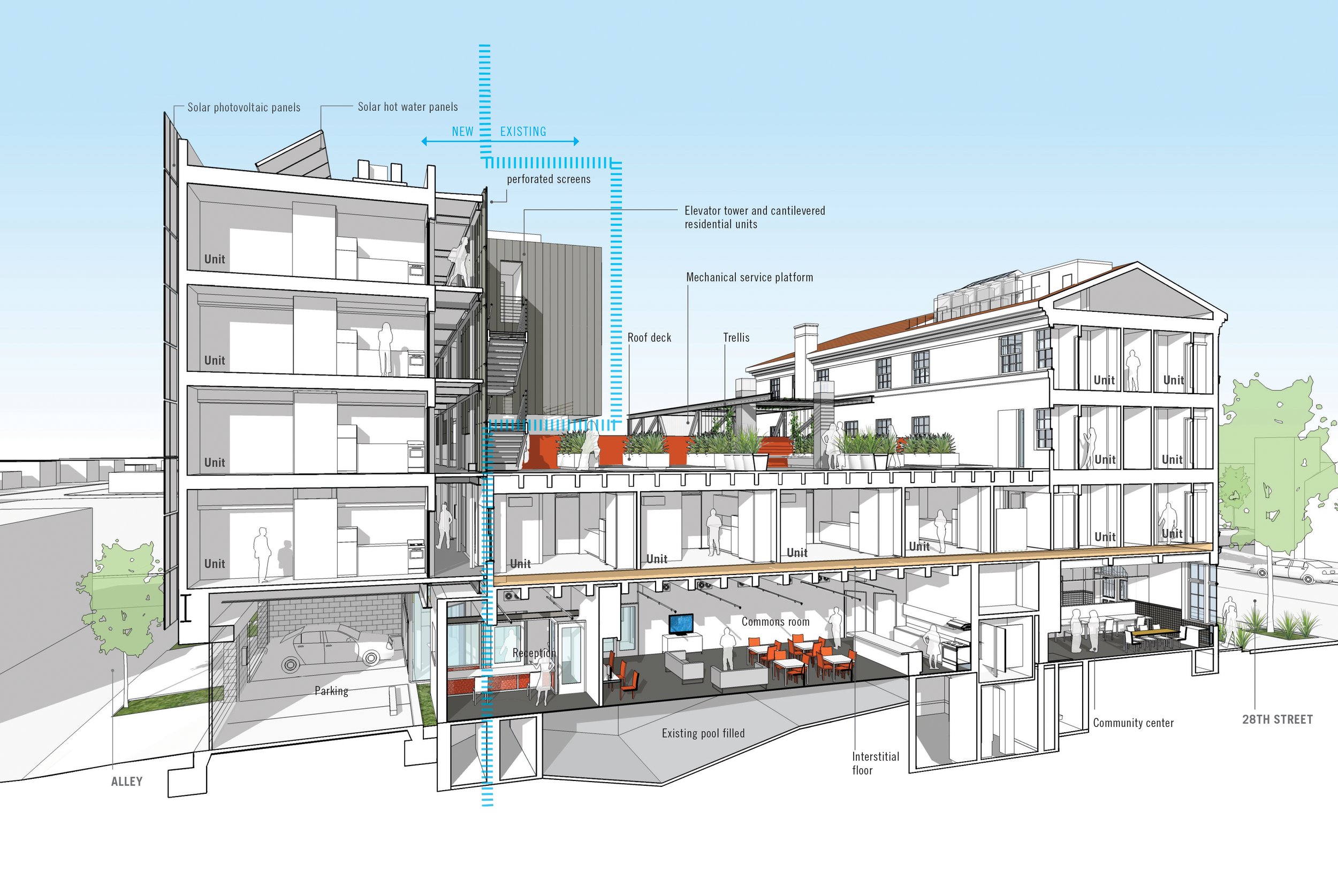

Respect and Boldness

The 28th Street YMCA combines old and new in a way that is both respectful and daring. The Williams building, now gracefully preserved, and the new housing are connected via a structure that serves as both bridge and an open roof terrace seating area, vividly painted red with planters and seating. What is invisible to passersby is the complicated fusing of old and new building systems (structure, plumbing, etc.) that the architects pulled off to make the project succeed.

Looking forward, looking back

They also added a dash of contemporary style that doubles as thermal protection: The south-facing facade of the addition has a wall of dark-blue photovoltaic panels to provide shade while they absorb the sun. On the north side are perforated metal screens, in which sharp-eyed viewers might spot a pattern echoing the cast stone reliefs of the Williams’ building. “Working with historic buildings is as much about looking back as it is about looking forward,” says project architect Brian Lane. The goal is to improve and add in ways that are “respectful and compatible, but at the same time establish a conversation between old and new that reenergizes the building and community around its next life.”

How did they do it?

Behind the rebirth of 28th Street Apartments lies a long and complicated gestation, involving numerous agencies, funders and individuals. When the surrounding area went into decline, the Community Redevelopment Agency of LA (CRA/LA), now defunct (see Playbook), designated it a “redevelopment zone,” meaning they could stimulate investment through grants or below market rate loans to developers. Revenues from growing taxes would then be plowed back into the community.

The total development cost was $27.7 million. The financing for this project required a complex “capital stack” of multiple public and private funding sources, including: Wells Fargo Bank; California Housing and Finance Agency (CalHFA); Department of Mental Health Services (MHSA); Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD); Community Development Block Grant (CDBG); Affordable Housing Trust Fund (AHTF); HOME Investment Partnership Program (HOME); Los Angeles County Development Authority (LACDA): City of Industry Funds; National Equity Fund (NEF): Tax Credit Allocation (TCAC); Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA/LA).

Paul R. Williams Apartments

Address: 1010 E Jefferson Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90011

Developer: Hollywood Community Housing Corporation

Architect: Angelus Funeral Home, Paul R. Williams; Adaptive Remodel: Adaptive remodel and Paul R. Williams Apartments: Milofsky and Michali Architects (M2A)

Contractor: Dreyfuss Construction

Date: Angelus Funeral Home, 1934; Paul R. Williams Apartments, 2019

Type of housing: 100% Affordable

From Funeral Home to House and Home

Just minutes by car south from 28th Street Apartments is another fusion of historic heritage and housing: the 1934 Angelus Funeral Home, designed by Paul R. Williams in a neo-classical style, together with two apartment buildings added in the late 20-teens.

The nonprofit housing developer Hollywood Community Housing Corporation and architects M2A repurposed the former funeral home as management offices, seven living units and community spaces. They added two adjacent buildings, with 34 large family units in two adjacent buildings, all styled to be compatible with the historic Paul Williams-designed funeral home.

What Makes it Awesome?

The Angelus Funeral Home was in such a state of disrepair that it had been boarded up for years, recalls Victoria Senna, Director of Housing Development for Hollywood Community Housing, in this film about the project, made by FORT: LA founder Russell Brown. The architects M24 found the “character-defining” features that denote the hand of Paul Williams – graceful circular stair, slender classical columns and proportions – and let those guide the retrofit. “To rehab this gorgeous building and to help revitalize the neighborhood because you’re revitalizing part of its culture and a part of its history, and in the meantime you’re providing housing to these families, it’s kind of a perfect world,” says Senna. For a resident, Melanie Hernandez, unused to a secure home with nice countertops and her own key fob, the place makes her “feel like Royalty.”

How did they do it?

As with the other two projects, piecing it all together was a puzzle. The $21-million development drew on funding from Wells Fargo, City of LA Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), Housing Department HOME funds, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits. The project also made use of the Federal Rehabilitation Tax Credit, which required all the work to meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation.

Dunbar Village

Address: 1068 E. 42nd Place Los Angeles, CA 90011

Developer: Dunbar Hotel, Builder/Owner: John and Vada Sommerville; Dunbar Village, Thomas Safran Associates (TSA)/Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD)

Architect: Dunbar Village, TSA/Withee Malcolm/BSB

Contractor: Westport Construction/ICON Builders

Date: Dunbar Hotel, 1928; Dunbar Village, 2013

Type of housing: 100% Affordable

Listing: LA Housing Department, Affordable and Accessible Housing Registry

Dunbar’s Dazzling History

Central Avenue between Olympic and Slauson in the 1920s through the ‘40s was dazzling. Here were lights, crowds, and nightlife. The strip was known as “Brown Broadway,” and jazz greats from Jelly Roll Morton to Charlie Parker and Miles Davis performed to mixed audiences at the Cadillac Cafe, the Downbeat, Club Alabam, the Last Word, the Lincoln Theater, Jack Basket Room and more.

Then there was the Hotel Somerville at 42nd Street, built in 1928 by John Alexander Somerville. It was imposing, with a red brick and cream facade with decorative plasterwork framing a grand doorway, and a grand reception area with high arched windows and an immense chandelier. It was soon renamed the Dunbar, for the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar; in 1931 a new owner, Lucius W. Lomax, Sr, added a cabaret. The NAACP held its first West Coast convention there, and the space became a haven for writers, performance and thinkers, including Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Thurgood Marshall, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. “This was the place where the future of Black America was discussed every night of the week in the lobby,” Celes King III, whose family owned the building at one time, told KCET.

From Hotel to Home

This Black-owned and built hostelry was a magnificent oasis from the demeaning segregated hotels and boarding houses of the time. It became an anchor for South-Central Los Angeles, an area to which many African Americans were confined during Jim Crow by zoning, redlining and racial covenants. But when those restrictions were outlawed, Black Americans moved to other neighborhoods, and this cultural hub lost its centrality. The Dunbar Hotel and its surroundings fell into decline; by the 1980s it was attracting uninvited guests: pigeons, rats and drug dealers.

Stop by Dunbar Village today and the razzmatazz has gone, but following a painstaking restoration, the retrofitted Dunbar Hotel and Somerville North and South, companion buildings on the next block, Dunbar Village offers 83 dwellings for seniors and families, ranging from studios to four bedrooms, who pay rents tailored to very low and low income earners.

What makes it Awesome?

The former Dunbar Hotel brims with renewed pride, from its skylit lobby with flagstone floor, a tinkling, tiled fountain and shiny ferns to the balconied reception area where jazz luminaries once performed, now sporting vases of fresh cut flowers, deep armchairs, a grand piano and a billiard table (accessories found in most TSA properties. If Dunbar residents want to grab a coffee, they can drop into Delicious at The Dunbar, a cafeteria in the street-facing, ground-level retail. A veteran who we meet on visiting says it gives him a new sense of place.

How did they do it?

As part of the CRA/LA’s redevelopment zone, Dunbar Hotel was transformed into affordable housing in the late 1980s, and the two adjacent buildings, Sommerville I and II, were added in the early 1990s. But all three fell into disrepair and by 2009 they had been foreclosed on. The city launched a Request for Proposal (RFP); Thomas Safran and Associates (TSA) and the Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD) submitted a winning proposition: “Dunbar Village,” an intergenerational community for seniors and families, with “community benefits” including a pocket park, commercial space, a child care facility, local resident construction and street beautification jobs, and a computer lab.

The project cost $23.7 million. The team had to corral multiple sources of public and private funding, or “capital stack,” as part of construction and permanent financing to maintain the buildings: Wells Fargo Bank, CRA/LA, Union Bank Historic Tax Credit Equity; California Community Reinvestment Corp.; Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (California Tax Credit Allocation Committee); Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD); Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) project based vouchers.

Paving the Way for more Adaptive Reuse

The Dunbar Village, the 28th Street YMCA and Paul R. Williams Apartments have all received numerous awards, and they show how to repurpose existing buildings in ways that solve for housing, sustainability and architectural and cultural preservation.

With those goals in mind, the City of LA is in the process of expanding its 1999 Adaptive Reuse Ordinance (ARO), to apply it to more modern buildings and a wider range of building types, including office buildings, retail malls and parking structures. This ordinance was originally focused on Downtown Los Angeles and enabled the conversion of thousands of defunct historic office buildings to become market rate rental homes and condos. Adaptive reuse is a high priority in the City’s multi-pronged efforts to meet its Housing Element requirements (see Playbook).

Call To Action

1) If you believe in projects like Dunbar Village, 28th Street YMCA and Angelus Funeral Home / Paul R. Williams Apartments support efforts to transform older buildings into housing. Follow the LA Conservancy’s work in this area, and SCANPH, which represents nonprofit developers, several of which are actively engaged in adaptive reuse.

2) Participate in the public process at the City of Los Angeles that is currently updating and expanding its Adaptive Reuse Ordinance.

3) Show your love for great affordable housing by posting to IG when you see an example you admire, and tag it #AwesomeAndAffordable or #FORTAAA.

More about the developers

Thomas Safran & Associates (TSA)

Tom Safran got his start in the 1960s as an “urban intern” working on public housing, and then a housing rep for HUD, first in Iowa and Nebraska, then LA County. He established his firm as a for-profit, not nonprofit, developer, albeit he sometimes partners up with nonprofits. He established Tom Safran Associates in 1974 and now owns shy of 80 properties, with over 6300 units of luxury, affordable and mixed-use rental housing. Many are in adaptively reused or restored, older structures, as well as ground-up buildings that tend to evoke LA’s more traditional architectural heritage. He manages the complexes he builds. To supplement the below-market rents, TSA accepts Section 8 housing vouchers, and HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH).

Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD)

The Coalition for Responsible Community Development (CRCD), was co-founded in 2005 by Mark Anthony Wilson, Jr., now the agency’s President and CEO. He was raised in South Los Angeles, and worked with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference/Martin Luther King Legacy Association, before joining the Dunbar Economic Development Corporation, and then cofounding CRCD, with Ruth M. Teague, Noemi Soto, Fernando Miranda, and Hugo Ortiz. Their goal was to provide community development services in housing, education, and jobs for primarily Latino and African American youth in the Vernon-Central Los Angeles community, along with activism at state and local levels, to improve the policies, systems, and long-standing neighborhood conditions that impact young people’s lives in high-poverty communities. According to their website, CRCD owns and operates 14 developments with 464 units of affordable and permanent supportive housing with over 1000 more in the development stage. Three of their housing complexes are historic buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places: 28th Street YMCA, Dunbar Village, and the Historic Lincoln Theater (in pre-development).

Holos Communities

In 2005, Holos Communities, formerly Clifford Beers Housing, emerged from Mental Health America-Los Angeles. Named after the founder of Mental Health America, Clifford Beers Housing focused on developing permanent housing to ensure health and well-being for the most vulnerable. Spinning off into its own organization in 2015 and now known as Holos Communities, the organization today has 14 properties with nearly 600 apartments with wraparound supportive services, as well as three commercial spaces prioritized for BIPOC and women-owned businesses.

Led by Cristian Ahumada, the nonprofit was renamed Holos Communities for the Greek word, meaning holistic, to express the intertwining goals of ending homelessness, combating global warming, and reversing racial inequity through the design of spaces that provide homes, services and jobs while helping to strengthen neighborhoods and local economies. Ahumada has worked with innovative architects to push the envelope on design and planning. He’s also rethinking the nonprofit model of financing.

Like many other housing nonprofits, to date Holos has deployed Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) (see Playbook). However, this form of subsidy comes with red tape and various restrictions, and Ahumada is seeking new, faster, and more economic models of housing that do not rely on LIHTC.

Hollywood Community Housing Corporation (HCHC)

Hollywood Community Housing Corporation (HCHC) was founded in 1989, in response to deteriorating economic conditions in the Hollywood area, an increase in the number of low-income families living in cramped conditions, and a shortage of affordable housing options. At that time, historical properties were being targeted for demolition by developers and replaced with lucrative, but lower-quality, bland apartment buildings. So, then City of LA Councilmember Michael Woo, along with the CRA/LA and the Los Angeles Community Design Center brought together local stakeholders, historic preservationists and concerned residents. This effort resulted in the creation of the Hollywood Community Housing Corporation (HCD). Since then, HCHC has developed 33 properties, with 1,244 affordable rental homes that combine on-site supportive services for low-income families, seniors, veterans, persons with disabilities and people who have experienced homelessness. Though it originally focused its development efforts in the Hollywood area, it has branched out to other communities in Los Angeles County, including South Los Angeles.